Fook Hai: The City has Many Pockets

In this Insight piece, Chew Yunqing shares the authentic and unexpected urban encounter of a weekend flea market inside Fook Hai Building, one of Singapore’s many aging strata malls, reflecting on how such spontaneous appropriation of pocket public spaces enrich our urban landscape.

Images by Fabian Ong

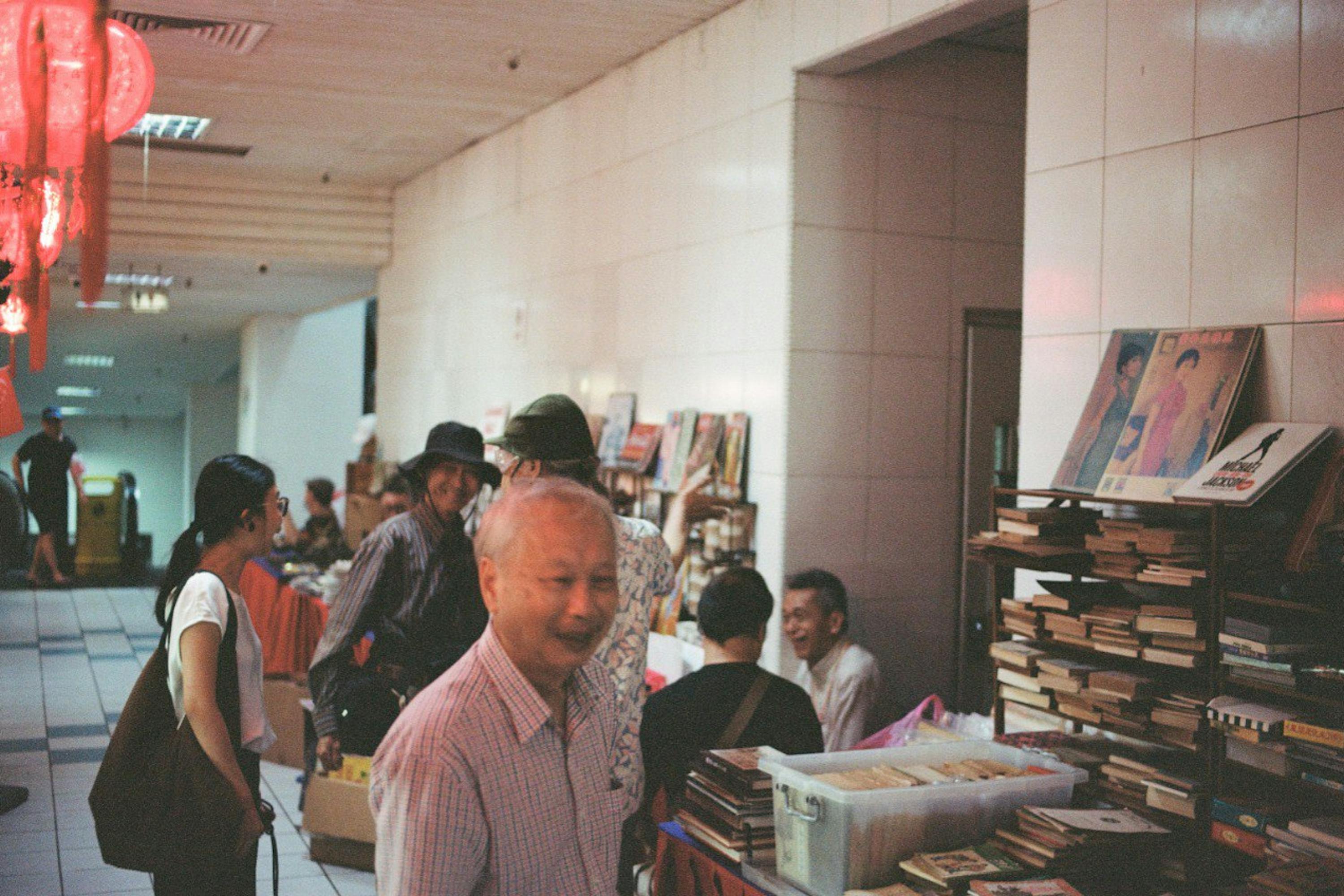

Fook Hai Building, a walk-in wunderkammer

Growing up in Singapore, the desire to seek out something odd, surprising, or even forgotten is probably relatable. It doesn’t matter if it is a place or a thing, but one day I encountered the intriguing coincidence of both in the form of the Fook Hai building. While its name in Chinese ('福海') translates to 'sea of luck’, what materially greeted me was a charming riot of second-hand ‘barang’ (Malay for ‘goods’) of jumbled origins: some sit neatly amongst shelves behind shop windows; others stack with some entropy on the itinerant stands along corridors; the rest gather on islands of tables at the central atrium. Amidst this sea of particulate ‘vintage’ matter of volatile values was the merry chatter that emanated from its frothy mix of sellers and visitors.

Seeing this animated flea/antiques/collectibles community occupy an unassuming mall in downtown Singapore inspired much thinking about how our city, even with its appetite for legibility and control, still has unexpected (and perhaps unconscious) tolerances for the flavourful informal to accumulate. At Fook Hai, I observe firsthand the workings of such ‘pocket’ spaces, which I use to describe the smaller but nonetheless public spaces that lace the broader infrastructures and flows in the city, rather like the pockets stitched to our trousers.

Seeding a Pocket Heterotopia

‘Pocket’ spaces seem to develop from humble ‘left over’, not necessarily unplanned but simply unnamed bits of our city. Fook Hai offers such a space. Built in 1977, it belongs to the class of postwar modernist structures whose flashier counterparts include the Golden Mile Complex. Fook Hai, however, is relatively modest in both form and provenance; stripped of its colourful contents, it looks like a typical strata-titled mall. Since it is not an architectural ‘icon’, it receives little general attention. Its humble size for a mall has also meant that the building, with the consensus of its owners (which are relatively few), has been quite free to adopt this flotsam of secondhand affinities.

This titration of ‘barang’ and its associated communities into Fook Hai that blurs the distinction between ‘private’ and ‘common’ spaces would have been unimaginable at conventional developer-managed malls, whose pursuit of mass appeal with the goal of profit maximisation means that their programs and spaces are tightly calibrated and regularly ‘refreshed’.

At Fook Hai, a different logic of efficacy is at play. Many of the shops in permanent units are unrelated to the collecting community and close on Sundays. The related ones remain open. An additional group of sellers set up stalls at $35 per table in the common areas. Fook Hai as a collectibles trading community pocket then comes into life. Such manoeuvres are only possible when its host space is open enough to support ground-up adjustments and appropriation that generate their own relevant spatial programming, which in Singapore’s context might be most feasible in strata-titled spaces.

People in the Pocket

The fluctuating value of a second-hand object mirrors that of the perception of a building like Fook Hai—unnoticed by most, Fook Hai is simultaneously a cherished ‘port of call’ to the ephemeral movements of second-hand goods. While the objects come and go, a critical crust of people, liaisons, and habits has accumulated here. This suggests that ‘pocket’ spaces are the active product of an invested demographic, with easily expressible needs and routines fronted by representatives. Mr. Poh, the owner of a permanent shop, “Viewpoint Trading and Collectibles," facilitates Fook Hai’s weekly Sunday arrangement to host additional sellers. He interfaces between the strata management and the Sunday sellers on matters like the location of each seller’s table and collects monthly rental payment from them.

The backgrounds of these Sunday sellers are as varied as their items: a former lawyer has been unloading his collection of English tea sets, colonial-era paraphernalia, and Peranakan jewellery; a decades-long career ‘karang guni’ Long Ke once literally struck gold while clearing out a house and collects oddly shaped lighters. There are also frequent visitors, like Mr. Yang, who partake in the atmosphere by chatting and ambling around. He is a former Chinese antique porcelain dealer and a member of the Red Packets Collecting Association. Notably, they not only gather within the mall but also settle at the coffee shops along its perimeter and sometimes at the neighbouring Chinatown Point mall too.

It is this community of dealers and collectors, whose friendships and familiarity extend long before they took up residence at Fook Hai, that continually nourish these networks of second-hand belongings.

Pocket Maintenance, Clockwork Care

An easy-to-overlook aspect of the ‘pocket’ space is the schedule of care that keeps it tidy and viable. This involves well-established rituals of use and storage of collective assets that are implicitly known by all. By 5pm, the Sunday sellers pack up and dock the tables and stools neatly to the space beneath the escalators at the atrium, which they have appropriated into a communal pantry with antique teak furniture. There are no attempts to conceal these items from common view or to lock them up, indicative of the trust that underlie such comfort in openness. Even the toilets are fastidiously clean with tissue rolls well loaded (unusual for many aging strata malls). Although such pocket spaces are the result of ground-up initiation, they can, using economical means, be kept highly organised.

Pocket spaces makes the city a home to all

Just like how our homes are only recognisably ours when they bear the imprint of our dispositions and particularities, for spaces to be comfortably ours at the scale of the urban, they cannot be homogenous either, as what is familiar can vary for different people and sometimes be at odds with one another. To have inclusive urban ‘living rooms’ entails viewing differences not as transgressions but as the seeds of authentic collective spaces where people can easily establish themselves in. One could even argue that pockets truly seed life in the city, as the lively must be diverse as a whole and specific in its parts. But difference does not mean divergence; pocket spaces must be spatially and socially ventilated and connected to the rest of the cityscape to remain vibrant.

While spaces that are open to all (e.g. community centres) are necessary to form a unifying baseline, it is equally vital to give space to the expression of more variegated needs and interests that appeal to segments of the population, in this case the collecting community. Luckily, pocket spaces are small, and don't need much, and it might actually be more efficient to just let them happen on their own. When groups of people with shared interests can, using the language, rhythms, and means that they know best, fashion spaces of belonging that often elude generic pre-determinations of usage, our cityscape is enriched with not only the capacity to conduct movements but also for meaningful encounters to collect.

Chew Yunqing is the founder of Don’t Matter Labs, a spatial theoretical research platform to question what really matters. This essay draws from the ongoing research ‘Barang Barang- networks of belonging(s)’ that studies how and why we are attached to objects and environments through spatial and ethnographic documentation.