The City Resilient

People have been building cities for many millennia, yet it is only in this century that the urban populations have outnumbered the rural. Altogether, we are almost 8 billion people on the planet, and we can no longer rely on nature to balance our impact on the environment, to help us rebound when we have depleted the land of its resources. Therefore, more than ever, we need an urban resilience.

But what is urban resilience? The term “urban” refers to the city; a place where a critical mass of people have come together to live and work in close quarters, sharing resources, and finding, if at times ephemerally, a sense of community with one another. “Resilience” means the act of rebounding; the ability to succumb to stress, to break and to fracture, only to emerge in a stronger, better form, like a phoenix rising from the ashes or a reed that bends in the storm.

Put the words together and what appears is an idea of a place that is both a human settlement and a force of nature. The City Resilient is an alluring vision for 21st century urbanism. It speaks of strength and survival. It speaks of longevity and legacy. It speaks of vitality and victory in the face of adversity. But here’s the catch: Though it’s true that an individual person can be resilient, urban resilience is a concept that can only succeed at the scale of the collective. And from the individual point of view, the vision might not be quite as idyllic as we first imagined.

The phoenix is a mythological bird that goes up in flames when its time has come, only to be reborn again from the ashes. In the real world, there are no such birds. Instead, there are plants and trees that have come to rely on periodic fires in order to release nutrients, hatch their seeds, or access sunlight. From the point of view of the individual tree, wildfires may seem incredibly destructive. But the collective ecosystem still needs them in order to survive.

It’s a grim example, I know, and perhaps a bit extreme. Still, it goes to illustrate an important point, which is that in any living system, old components must sometimes perish for new ones to flourish. In nature, this process occurs entirely organically. But what happens when the components are controlled not by the environment, but by conscious human beings? By people who have a sense of free will, and the choice to either start the fires, or put them out (figuratively speaking, of course).

Imagine that, instead of a tree it was your business, and instead of a fire it was a closure, and instead of the seeds hatching, it was your children prospering. Would you close your business if your children’s wellbeing depended on it? What of your neighbour’s children? This is not an abstract moral dilemma. Across the world, there are thousands of businesses that do little to contribute to the collective resilience of our cities, let alone our planet. But maybe you don’t own a business. Maybe you just drive a car. Or fell trees that overshadow your garden. Or build towers where the city needs a park. Or object to residential construction amidst a housing crisis. When the wellbeing of the collective is at stake, what then, are you personally prepared to sacrifice for the City Resilient?

Ultimately, this is not a choice we get to make. In recent decades it has become very clear that there are stark planetary boundaries around our options, an ozone ceiling above our ambitions. In order to create truly resilient cities, we must ourselves become resilient, allowing old systems and mindsets to crumble so we can build new, better ones. In this transition, there are three important aspects to remember.

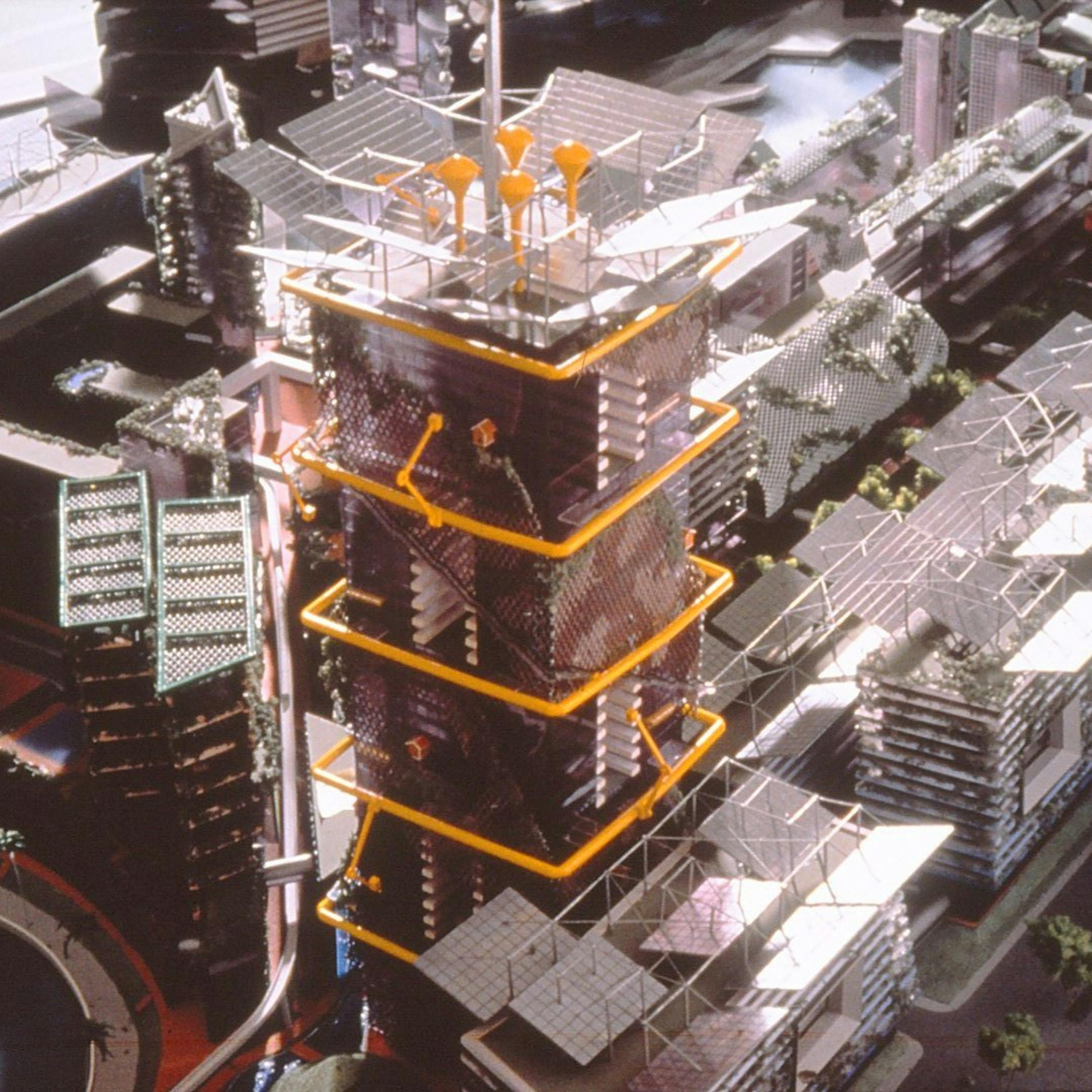

First, remember that change is inevitable. This is an important circumstance, but not one that is easily embraced by the built environment industry, nor is it particularly compatible with our current construction techniques or material choices. Nevertheless, things do change, be it our work-life patterns during a pandemic, the risk of a site flooding, or our sources of energy. Therefore, for the city to be resilient, places and buildings have to be adaptive.

The second point is that the smaller the components are, the lesser the disruption of change will be. Imagine a building becoming unfit for purpose. Do you replace the entire structure or merely some of its parts? The latter solution is obviously both more economic and more sustainable – if you planned for it. Small is also human. By making components at the scale of a person, we are creating opportunities for communities to interact with the urban environment. If we want our places and buildings to be adaptive, they have to be dexterous.

The last point comes back to the notion of free will. Unlike nature, which is governed my natural selection processes, the City Resilient relies on people to make active choices in order to evolve. If something isn’t working, we are the ones who must have the courage to set it on fire (again, figuratively speaking) and try again. A person who has owned a car their whole life will need a degree of resilience to learn how to ride the bus. A building owner who is used to signing 20-year leases will need a degree of resilience to retrofit their stock for the on-demand economy. It is clear that for places and buildings to be dexterous, they must be governed by resilient users.

At present, global temperatures are increasing faster than ever, heat waves, heavy downpours, and major hurricanes are becoming more frequent, and sea level rise is threatening to swallow over 570 low-lying coastal cities world-wide. Looking ahead, the City Resilient is the only possible urban future we can hope to build for ourselves. But in the short-term, I can’t help but wonder if the large-scale, fragile system we currently have – and the behaviour that supports it – is at all capable of change.