Towards a Regenerative Future

“Stop calling me resilient. I’m not resilient. Because every time you say ‘Oh, they’re resilient,’ you can do something else to me.”

This is what New Orleans-based civil rights attorney Tracie Washington told writer Naomi Klein five years after Hurricane Katrina devastated her city.

Do words matter? In this moment of compound global crises, we surely need to move directly to action. The urgency becomes clearer with every new wildfire and flood; the scientific evidence clearer with every new intergovernmental report, most recently the IPCC’s Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, dubbed a “Code Red for humanity” by UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

However, it is our shared premise, as we express in our new book Flourish: Design Paradigms for Our Planetary Emergency, that in complement to other immediate actions to maximise our agency within our personal and professional realms, one of the most effective ways to seed action of the scale and scope required is to change our words, or more precisely, to change the stories that we collectively inhabit in the course of our personal and professional lives.

As the cognitive neuroscientist George Lakoff has argued, the metaphors we use to describe reality are not just a powerful form of framing; they substantially shape our reality. In our book we articulate the overarching need for those of us working in the built environment to move beyond the story, or paradigm, of ‘sustainability’, whose power has been neutralized through overuse and misuse, towards a culture that is regenerative.

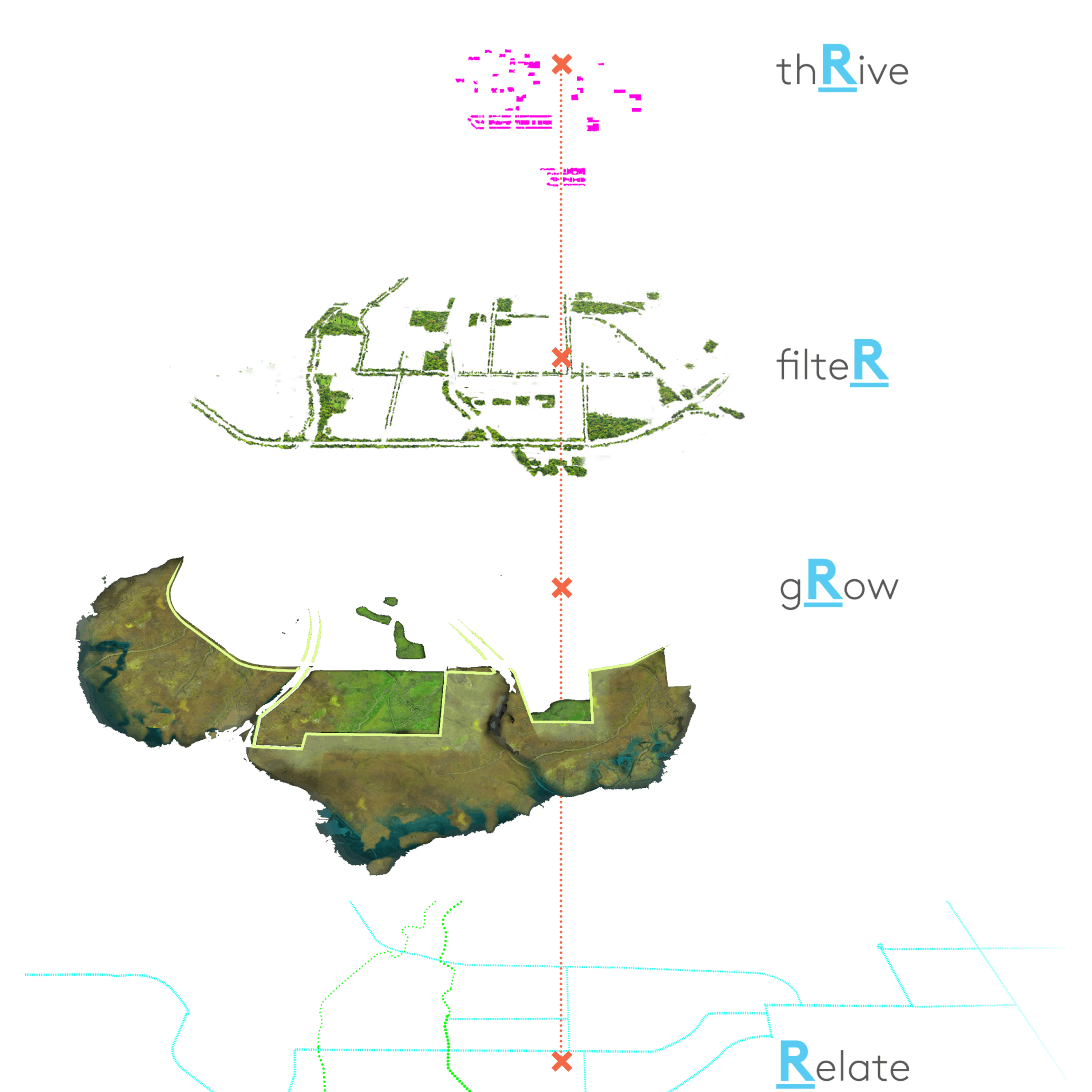

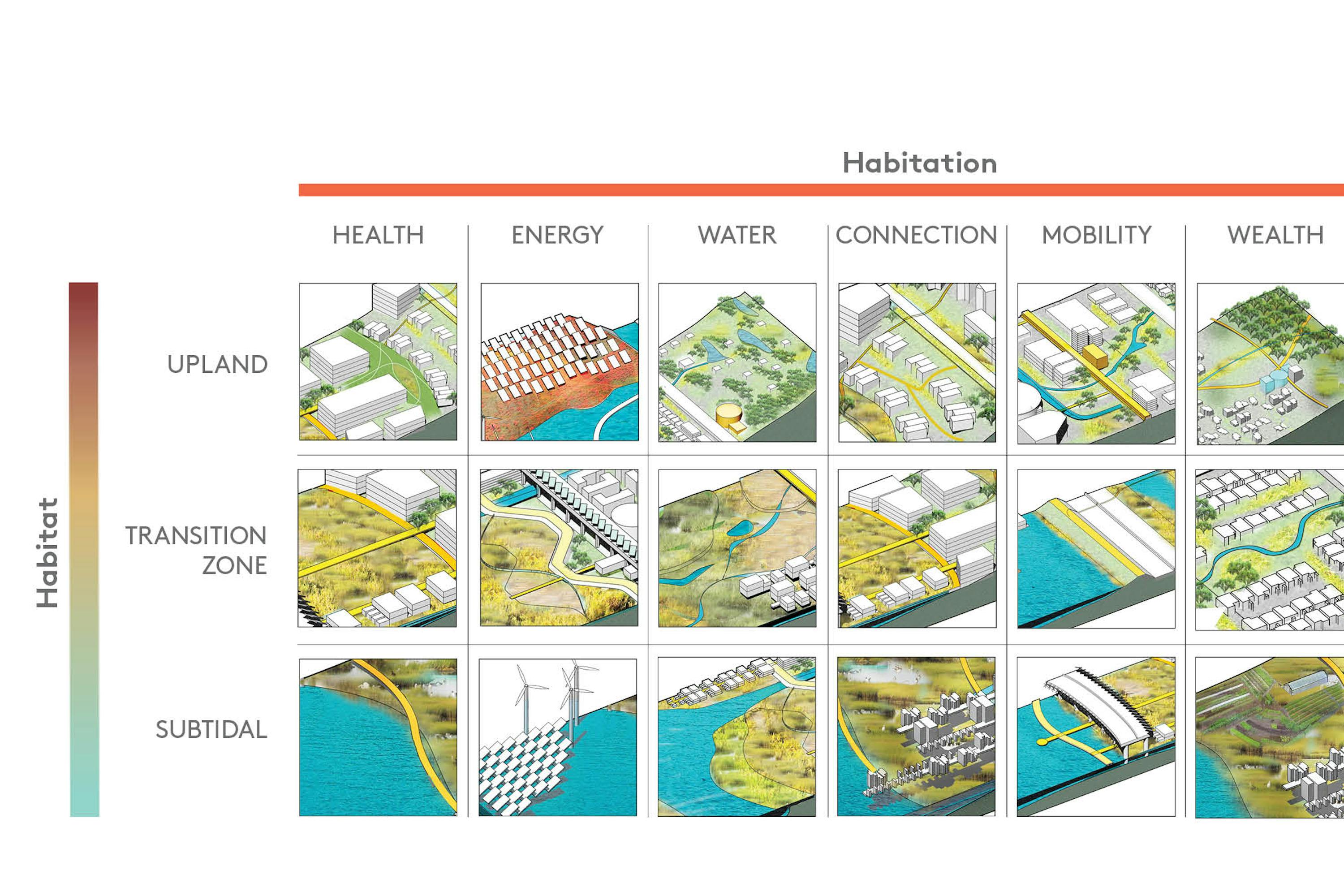

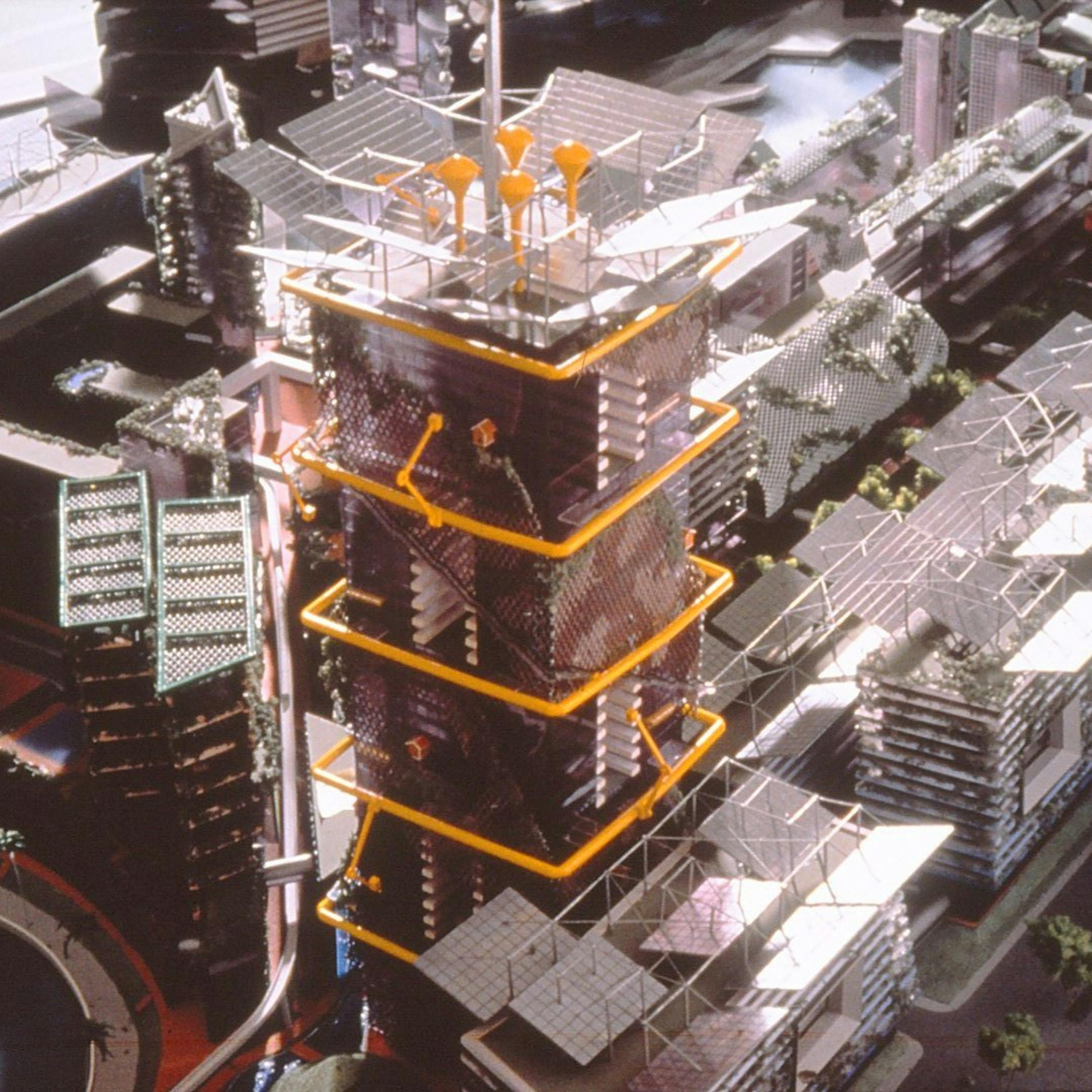

Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Resilient Cities Network. Sarah herself has been involved with two recent high-profile multi-city urban resilience initiatives: as a jury member for the Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge in California (2017-2018) and an advisory board member for Water as Leverage for Resilient Cities Asia in Chennai, Khulna and Semarang (2018-2020). These were inspiring, coalition-building and attention-drawing actions, with some important practical outcomes, some of the most promising of which are depicted in the images accompanying this essay.

However, we are concerned that, outside of academic discourse, some of the most commonly used definitions of resilience are more defensive than transformational. For example, The United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction defines urban resilience as “provid[ing]cities with operational tools for coping with acute shocks induced by natural and man-made hazards.” The World Bank defines it as “the capacity to plan for and mitigate adverse impacts of disasters and climate change.” The Rockefeller Foundation and Arup’s City Resilience Framework identifies “the capacity of a city’s systems, businesses, institutions, communities, and individuals to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of acute shocks and chronic stresses they experience.”

These framings of ‘resilience’ could be interpreted as “We’re heading for a serious storm but, if we batten down the hatches and stockpile sufficient supplies, we'll get through it”. If human-induced climate breakdown and mass extinctions were a temporary phase, beyond which we could see calm water, this approach would be appropriate. However, that is not the case; there is no reliable forecast for more stable conditions in the foreseeable future, in fact, on our current trajectory, we are intensifying the ‘storm’. The shocks and stresses are real, and require our attention to be sure, but a strategy of guarding against a growing list of threats is insufficient to our long-term survival.

More provocatively, philosopher Glenn Albrecht challenges common uses of ‘resilience’ as providing cover to “justify the ongoing existence of processes and activities that are driving humans to disease and extinction.” It would, in his view, be more accurate to refer to these as ‘negative resilience’, which occurs “where pathological social relationships that are oppressive and exploitative of humans and ecosystems (life) are rendered resistant to change by economic and political subsidies (donations and corruption) ... bullying, actual violence, terrorism and vested interests.”

In Flourish, we make the case for a different framing, asserting that our planetary emergency of climate destabilization and ecosystem degradation is so serious that we need to set our collective sights much higher. We need to transform the way we design, build, inhabit and manage the built environment so that we not only mitigate negative impacts (the approach that characterizes most design that is termed ‘sustainable’), and recover from shocks and stresses (the ‘resilient’ approach), but also make a net positive impact to repair the damage that humans have done to the rest of the living world.

As the environmental and human rights activist Rebecca Tarbotton put it: “We need to remember that the work of our time is bigger than climate change. We need to be setting our sights higher and deeper. What we're really talking about, if we're honest with ourselves, is transforming everything about the way we live on this planet”. It is no exaggeration to say that a full embrace of regenerative culture will be a turning point in human civilization and it is a point we need to reach as urgently as possible. The good news is that green shoots of regenerative culture are already visible around the world; indeed some of the work initiated under the ‘resilience’ agenda may produce ‘regenerative’ outcomes.

As we describe in Flourish, this will bring us closer to Indigenous wisdom traditions, which understand human culture as an integrated part of the web of life. It will provide a thrilling new sense of purpose for the designers, clients and inhabitants of the built environment. We explain why our new role should be “to support the flourishing of all life for all time” and what that means in both philosophical and practical terms.

We believe that it’s an essential part of the urgently required transformation of our culture, that we get our terms–and the shared practices that they underpin–right.