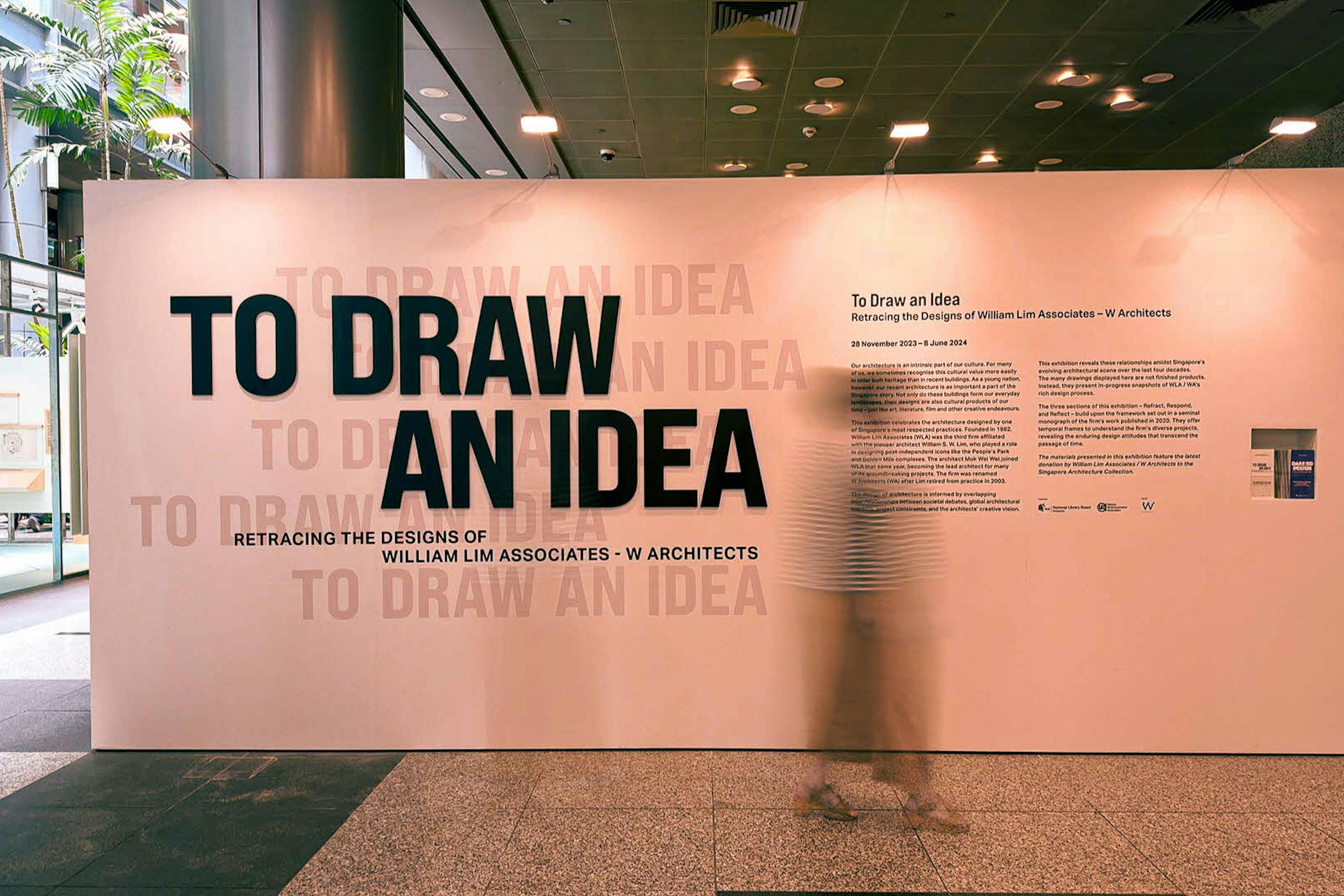

Reflections on ‘To Draw an Idea’ and the Production of Architectural Culture in Singapore

In this critical essay, Jacob Meyer shares his critical reflections of “To Draw An Idea: Retracing the Designs of William Lim Associates – W Architects” - the inaugural retrospective exhibition for the Singapore Architecture Collection (SAC) held at URA Gallery in the first half of 2024.

Images courtesy of Rachelle Su and Ronald Lim

The exhibition ‘To Draw an Idea: Retracing the Designs of William Lim Associates – W Architects,’ staged a year ago at the URA Centre, constituted an important moment in contemporary Singaporean architectural culture. It served both as a major retrospective of the work of Mok Wei Wei, regarded as one of Singapore’s most important practicing architects, and as the first exhibition produced with archival materials from the newly established Singapore Architecture Collection (SAC), curated by architect-curator Ronald Lim.

What is “architectural culture,” however? I would like to argue that architectural culture is produced by practices beyond the conventional act of design and includes researching, writing about, photographing, curating, and exhibiting architecture. Architectural culture requires these myriad practices as complementary to, but independent from design, to critically appraise and make meaning of built work. As theorist Sylvia Lavin has noted, the importance of exegesis—critical explanation or interpretation—means that these practices now constitute a significant form of architectural “work” themselves.

In line with this perspective, instead of appraising the work of architect Mok Wei Wei, which has been the subject of the exhibition, an accompanying catalogue, and a published monograph, I would like to focus on the curatorial successes of ‘To Draw an Idea’. By foregrounding aspects of architectural production often neglected by conventional elitist accounts, the exhibition charts a promising path, while revealing many latent opportunities that should continue to direct the production of critical architectural culture by the SAC.

Demystifying Architectural Labour

The most visibly novel curatorial gesture in “To Draw an Idea” is the conspicuous absence of the conventional “finished products” of architecture. Photographs of completed buildings, typically the focus of architectural exhibitions, are few and far between. Instead, the exhibition is largely composed of archival materials from the offices of William Lim Associates (WLA) and its successor, W Architects, donated to the SAC. They include hand-drawn sketches, plans, sections, axonometric drawings, construction documents, and correspondences.

The act of foregrounding these archival materials is significant as they demystify the labour of the architect, so often misunderstood in the popular imagination. Since the 15th-century treatises of Alberti, architectural labour has been distinct from the labour of building; yet architects are still synonymous and often credited with the authorship over a physical object they may have no direct role in realising. This logical leap, deeply ingrained in the architectural profession’s self-image, conceals the labour that is the real work of the architect: the development of design and the production of materials to support the realisation of design by others.

In ‘To Draw an Idea,’ the ‘real’ work of the architect is brought to the fore. In exhibiting the Church of Our Saviour (1985-87), an early Postmodern work by WLA, the central role of drawings as the primary output of architects’ labour is underscored by the display of various drawn materials. Notably, these drawings provide intimate insights into the architects’ working methods, offering a form of first-hand narration of the design and construction process. For example, coloured pencil sketches on butter paper reveal a search for form, composition, and colour as WLA grappled with the challenge of adapting a 1960s cinema into a charismatic church. Similarly, a hand-coloured elevation displays an intermediate stage of design resolution, accompanied by sketches of mounting details for signage that would adorn the auditorium's interior walls. Finally, an A1 reprographic blueprint of the building’s second storey, complete with annotations, white-out revisions, authority approval stamps, and signatures, alludes to the complexities of bringing a design to fruition while resisting simplistic narratives of design realisation.

Despite the challenges in exhibiting architectural drawings, whose legibility is often obscured by the complexities of drawing conventions and technical jargon, captions and the selective use of photographs help the untrained viewer understand these materials as ‘primary evidence’ of the architects’ process. In doing so, ‘To Draw an Idea’ effectively illuminates the reality of what architects truly do that is often forgotten. Doing so raises meaningful questions that can inform future curatorial approaches, such as: What other forms of labour go into a building’s production and how may these enter into dialogue with the materials produced by architects?

Architecture’s Contingency

‘To Draw an Idea’ also resists another sacred belief held by the architectural profession: the notion of individual genius and authorship. While it is commonly assumed that the design of a building can be wholly attributed to an architect, this is rarely the case. As architect and author Jeremy Till has noted, “architecture is defined by its very contingency” and is subject to a myriad of forces outside the architect’s control.

‘To Draw an Idea’ follows Till’s recognition of architecture’s contingency by dedicating a section of the exhibition, aptly titled “Respond,” to the external forces with which Mok has worked in productive creative tension. Among these external forces—such as the changing market position of private city-centre apartments and shifting public sector attitudes toward architecture—the recognition of design and planning regulations as perhaps the most pervasive, yet paradoxically unrecognised, force acting upon architectural production in Singapore is particularly compelling.

The introduction to ‘Respond’ frames Singapore’s specific planning processes, including Development Control and the ubiquitous abstraction known as Gross Floor Area (GFA). While these considerations might be dismissed as prosaic and unimportant to ‘high’ architectural culture, the exhibition highlights the pervasive commercial and regulatory logic imposed by GFA, as well as Mok's creative exploitation of this same logic to develop new formal approaches.

In the case of the Oliv, for example, the condominium’s strikingly verdant geometric front and rear elevations are revealed as a creative response to the bonus GFA incentives allocated to sky gardens. Mok leveraged this provision as an opportunity to provide spaces that, while compliant, feel like generous outdoor extensions of individual private apartments.

In foregrounding the role of design and planning regulations as agents in architectural production, ‘To Draw an Idea’ significantly unseats the role of the architect as the mythical sole author of the built environment, more accurately characterising them as a creatively responsive actor within a network of external forces. In the case of Mok’s work, this perspective enriches rather than detracts from his status as an architect, showcasing an ability to deftly balance real-world constraints and novel creative solutions.

Agents in the Production of Architectural Culture

Perhaps the greatest significance of “To Draw an Idea” lies not in its content—which deserves recognition for both Mok’s impressive oeuvre and Lim’s sensitive curatorial approach—but in the model it establishes for the production of architectural culture in Singapore.

For several decades, particularly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, architectural discourse in Singapore was enriched by a network of figures and institutions—an infrastructure of knowledge production— that went beyond the realization of buildings to include critical reflection on built work. Many of these contributors are featured in the exhibition, including the Australian critic Leon van Schaik, the journal Mimar: Architecture in Development, and the print version of The Singapore Architect. Together, these figures and institutions supported the “work” Lavin characterises as central to architectural culture that encompasses essays, criticism, interviews, exhibitions, books, and lectures. Unfortunately, interest in architecture as a ‘serious’ cultural discipline has been undermined by various forces, including social media’s prevalence and the shift from architectural critique to the primacy of the single ‘Instagram-able’ image.

In this context, the work of producing a critical architectural culture in Singapore—by critics, journalists, historians, theorists, curators, photographers, artists, and multi-hyphenate combinations of all the above—is urgently needed. “To Draw an Idea” is a promising step in this direction. The exhibition’s role in marking the emergence of the Architectural Curator in Singapore reflects institutional recognition for these specialised skill sets. Similarly, funding from the SAC, supported by NLB, NHB, and URA, establishes a much-needed model for public support of architectural culture, which has long been neglected in comparison to state-funded institutions for the visual and performing arts.

One hopes that the SAC can therefore build upon the successes of ‘To Draw an Idea’, supporting the cultivation of architectural culture in Singapore, while retaining its critical orientation so successfully adopted by Lim, in future exhibitions.

Jacob Meyers (b. 1999) is architecturally trained, and works at the intersection of conservation, research, and advocacy. He has served as an Architectural Conservation Consultant at Studio Lapis and is currently an Executive Committee Member of Docomomo Singapore. Jacob is currently pursuing a Master of Architecture at TU Delft, specialising in modernist heritage. All views are his own.

References

The Singapore Architecture Collection (SAC) is managed by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), National Library Board (NLB), and National Heritage Board (NHB), and comprises architectural models, photographs, drawings, artefacts, oral history recordings and more, contributed by architects, planners, urban designers and other professionals from the built environment industry.

Sylvia Lavin, “Showing Work”, Log 20: Curating Architecture, no.1 (Fall 2010): 5-10.

Mok Wei Wei and Justin Zhuang, Mok Wei Wei: Works by W Architects (London: Thames & Hudson, 2020)

Jeremy Till, Architecture Depends (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)